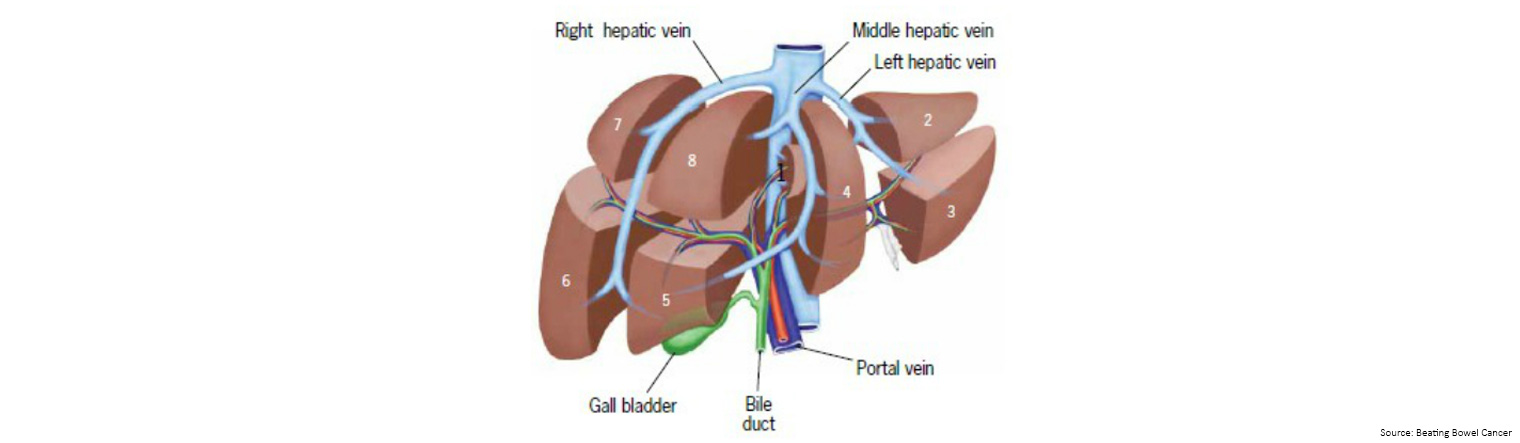

The liver is second only to the lymph nodes as the most common part of the body for bowel cancer cells to spread to. The liver is a common site for bowel cancer cells to spread to as the liver receives most of its blood supply from the portal vein (the vein that carries blood from the intestines and spleen to the liver).

If your bowel cancer has spread in this way, you have metastatic bowel cancer in your liver – not liver cancer.

Your treatment is dependent on where the cancer started and therefore the treatment you have must work on bowel cancer and not liver cancer cells.

The next most common part of the body for bowel cancer cells to spread to is the lungs.

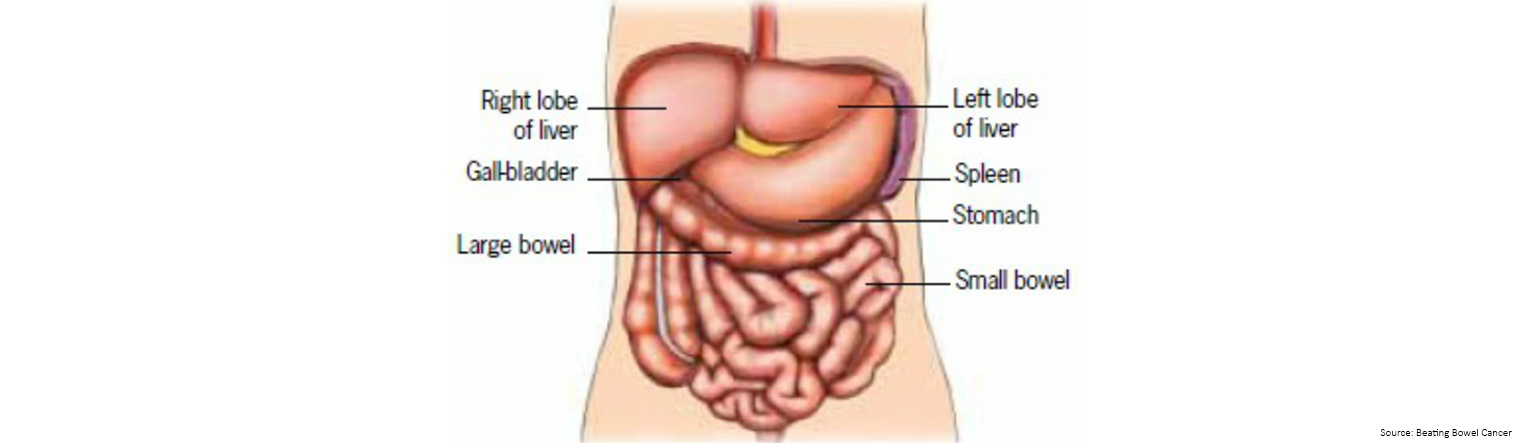

If you place your right hand over the area under the ribs on the right side of your body it will just about cover the area of your liver. It is divided into two main parts (left and right lobes). Each of these lobes is further divided into segments.

The liver is connected to the first part of the small bowel (duodenum) by a tube called the bile duct. This duct takes the bile produced by the liver to the intestine.

What does the liver do?

The liver is the largest gland in the body and has over 500 functions, which include:

- getting rid of toxins from your body

- processing chemicals from digested food

- producing bile

- repairing damage

- removing many drugs from the blood

Additionally, the liver has an amazing ability to repair and regenerate itself following surgery and will re-grow to its original size in about three months.

A diagnosis of metastatic bowel cancer in the liver can happen when you are initially told you have bowel cancer or some time after the initial diagnosis, during routine follow up, and may include one or more of the following:

- Blood test: blood test samples ('liver function tests') can be taken to see how well your liver is working and can be used to monitor patients for the early detection of metastatic cancer. By detecting metastatic cancer early, the treatment options can be greater and more successful.

- CT scan: a CT scan creates a cross sectional, 3D image of the body. The scan gives detailed pictures of the tumour(s) and surrounding tissues and organs, enabling the doctors treating you to gain an accurate picture of the tumour, and its location.

- Liver biopsy: your specialist may decide to take a small sample of tissue from your liver (a 'biopsy') to look at under the microscope. This procedure involves a very fine needle being passed into your liver, using a CT or ultrasound scan for guidance, and generally involves an overnight stay in hospital (due to the risk of bleeding associated with the procedure). You will receive a local anaesthetic to prevent pain.

- PET-CT scan: a CT scan can be combined with a PET scan which is a medical imaging technique which produces a three-dimensional, colour image of your body. When taken together, the results can be combined to show where there are any cell changes in the body, and whether the cancer has spread.

- MRI: magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) uses magnetic and radio waves (not X-rays) to show the tumour(s) in great detail and look at the blood supply to the liver. During the scan you will have to lie in the scanner for up to an hour, and, whilst it is very noisy, it is painless. Let the specialist know in advance if you are claustrophobic. You may be asked to drink a liquid 'contrast medium' before a CT or MRI scan, or be given an injection of a contrast medium during the scan (which may give you a hot flush for a few minutes). The dye travels to your liver to help produce a better image.

- Ultra scan: this painless test, which takes about 10 minutes, uses sound waves to build a picture of the inside of your liver and its blood supply. Sound waves from the scanner pressed onto your abdomen bounce off the internal organs, and echo back to make pictures on a computer screen.

It may be possible to remove the affected part of the liver with surgery and this is known as a 'liver resection'.

Only a relatively small number of patients with liver tumours are suitable for surgery, and whether or not this operation is an option for you depends on:

- whether the tumour in your bowel has been treated / is treatable

- how much of the liver is affected

- the size of the tumour(s)

- where in the liver the cancer cells are located

- how well the liver is functioning

- whether there are any tumours outside the liver, their location and how many there are

- your general level of fitness

If, following review of your scans and your clinical condition, the members of the Liver Multi-Disciplinary Team (MDT) agree that surgery is an option, this will be discussed with you. If surgery is not an option, the reasons for this will also be explained to you by your specialist. If the scans do not make it easy to see if you would benefit for liver surgery, the liver surgeon may choose to carry out a laparoscopy. This is a keyhole investigation which will allow the surgeon to 'look around' before deciding on the best course of action.

If surgery is an option, this is the best chance for long-term survival.

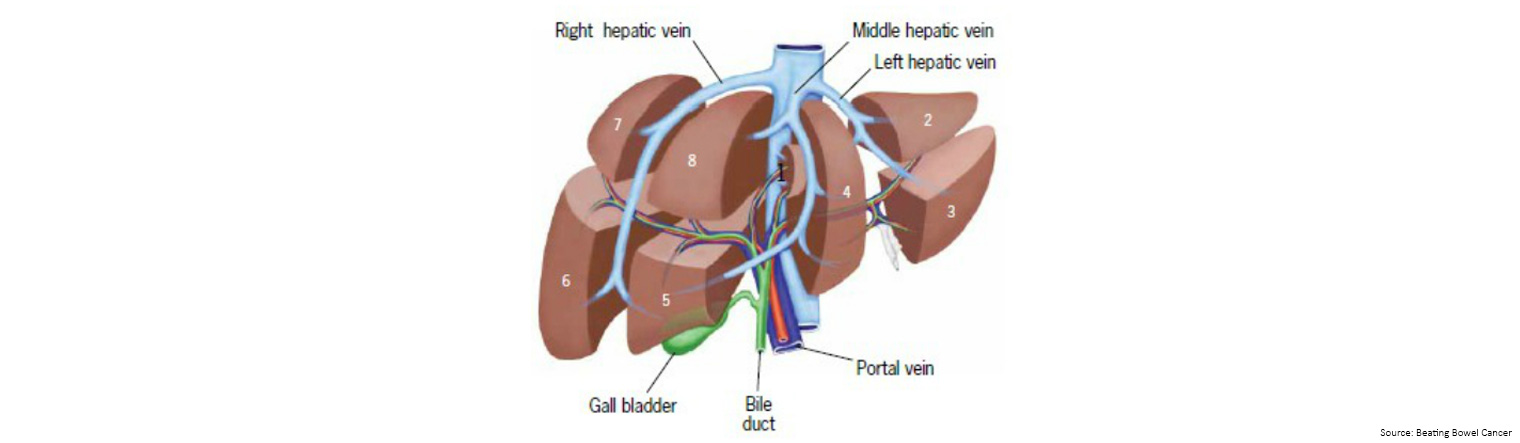

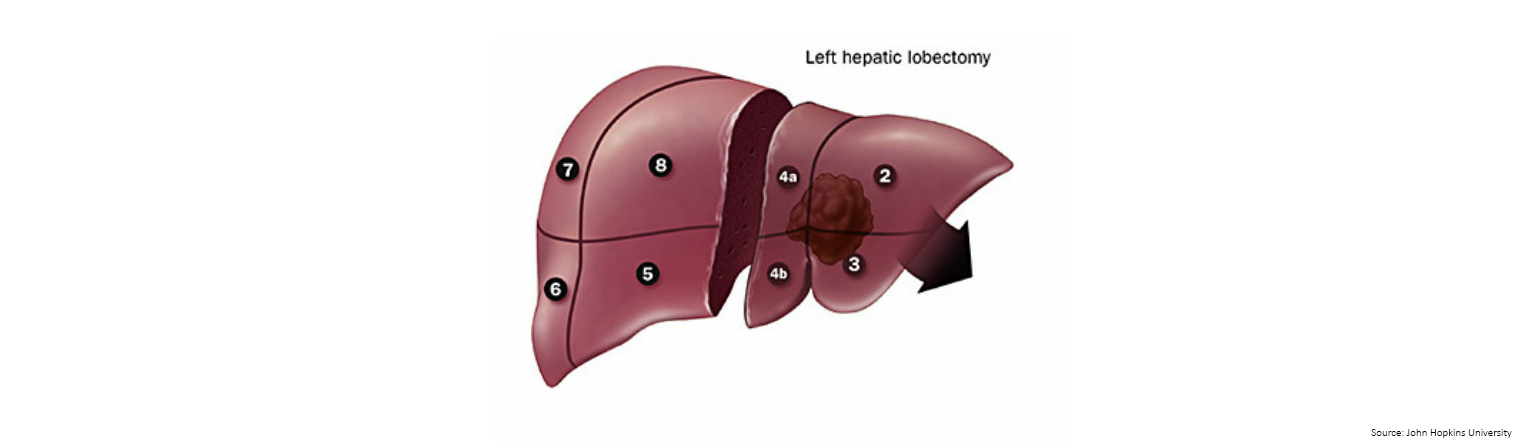

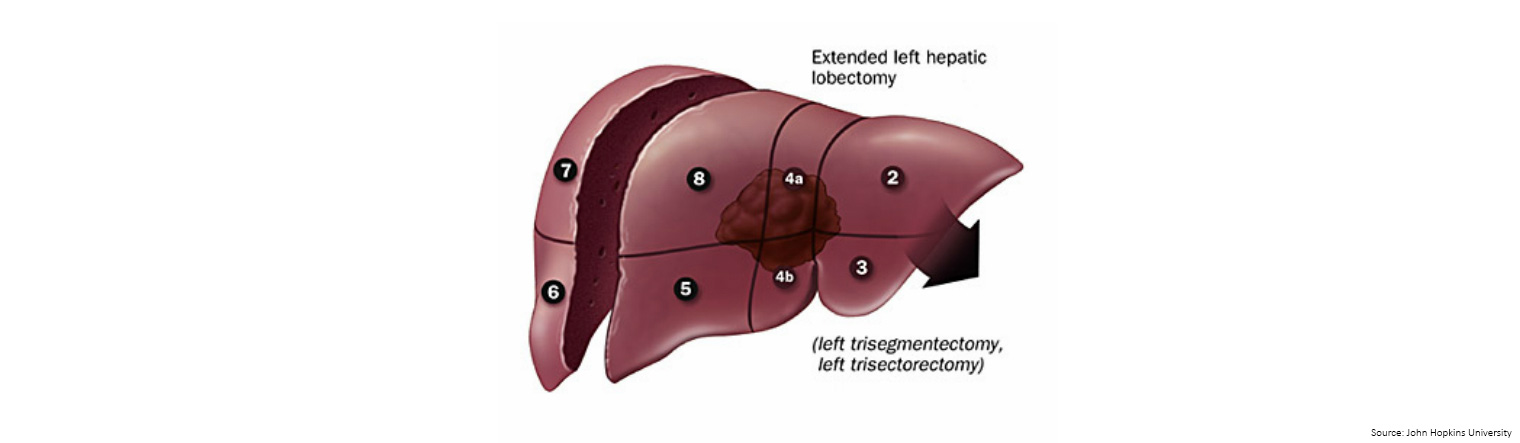

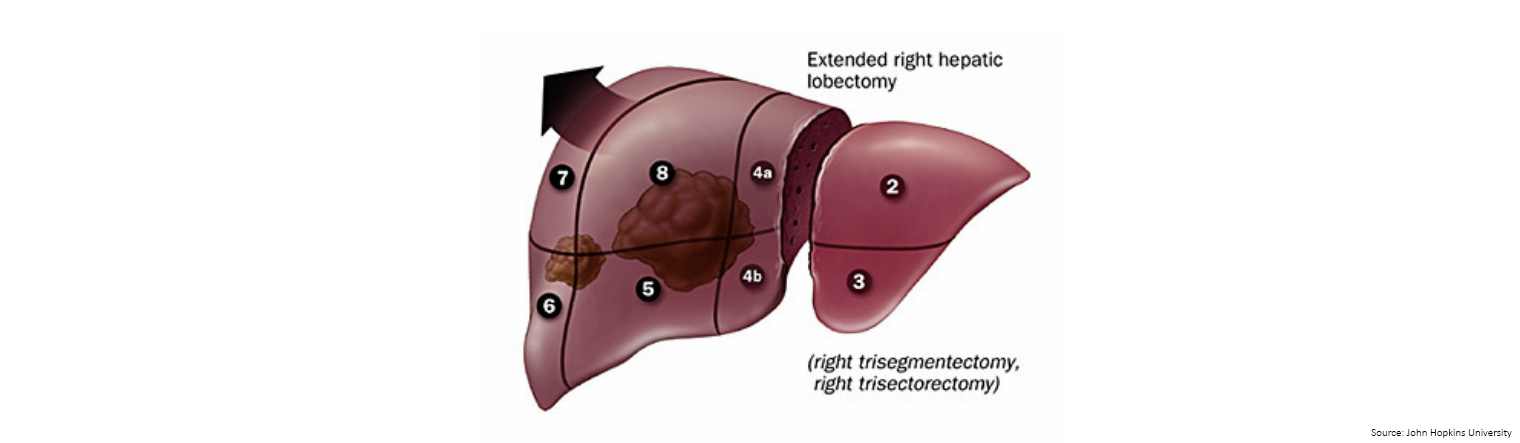

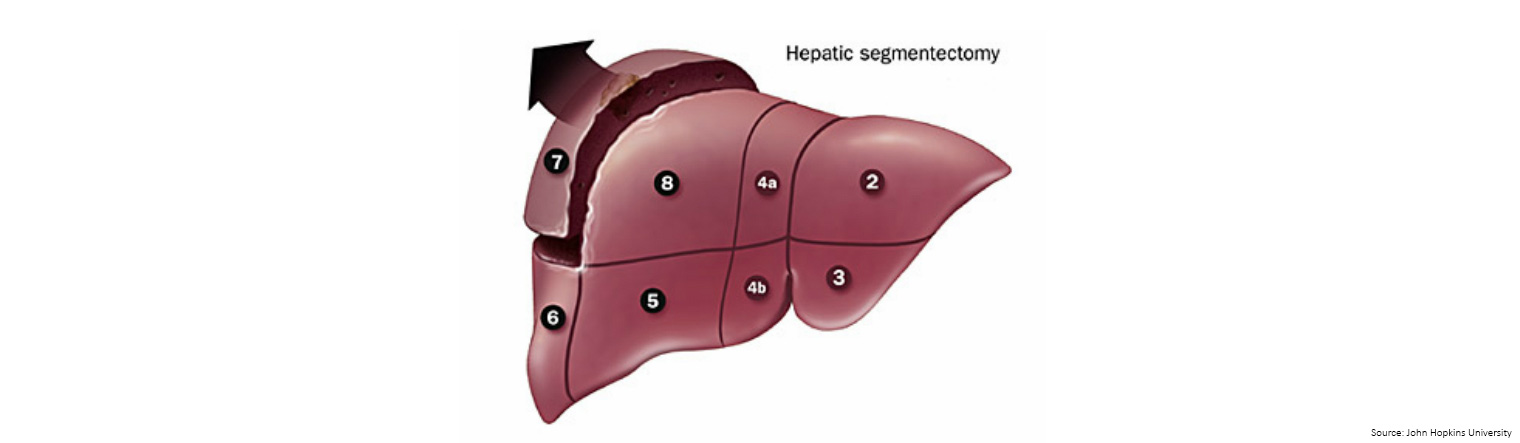

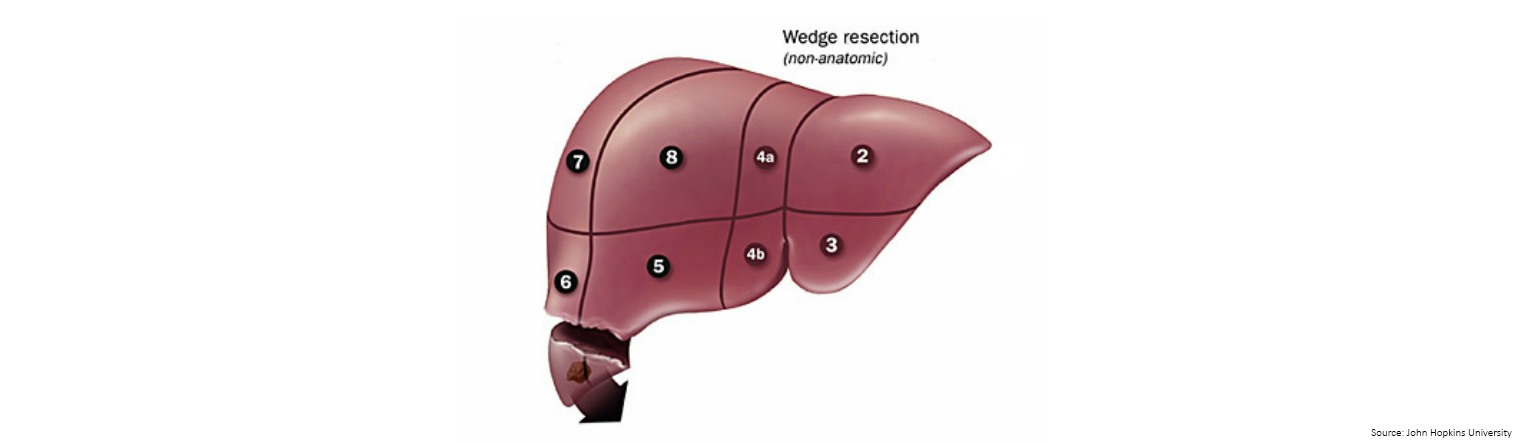

Increased knowledge of the different segments of the liver has led to the development of segmental-based surgery.

The liver can be divided into 8 segments: segment 1 is the caudate lobe, segments 2 through 4 form the anatomic left lobe and segments 5–8 form the anatomic right lobe.

Lesions confined to the right lobe are amenable to en bloc removal (removal in one piece) with a right hepatectomy (liver resection) surgery.

Smaller lesions of the central or left liver lobe may sometimes be resected in anatomic 'segments'.

Large lesions of the left hepatic lobe are resected by a procedure called hepatic trisegmentectomy (see diagram and explanation below).

When lesions are located peripherally (on the edges of the liver), hepatic wedge resection or anatomic segmentectomy are performed.

If a tumor is adjacent to or involving major intra hepatic vessels, resection of the entire segment or lobe is necessary.

Lobectomy is indicated when multiple lesions are located in different areas of one lobe.

Wedge resection is universally accepted for small superficial lesions.

Additionally, there are times when laparoscopic surgery is started but surgeons need to revert to open surgery during the operation. Liver resections usually take between 3-7 hours.

Risks of surgery

If you are suitable for an operation, your surgeon will explain to you that there are risks associated with liver surgery. These risks vary depending on the type of surgery you are having, the number and location of your tumours, your liver function and your general health.

If you do experience complications following surgery, you may have a prolonged stay in hospital including additional time in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU). Your surgeon will fully discuss your risks with you prior to the operation.

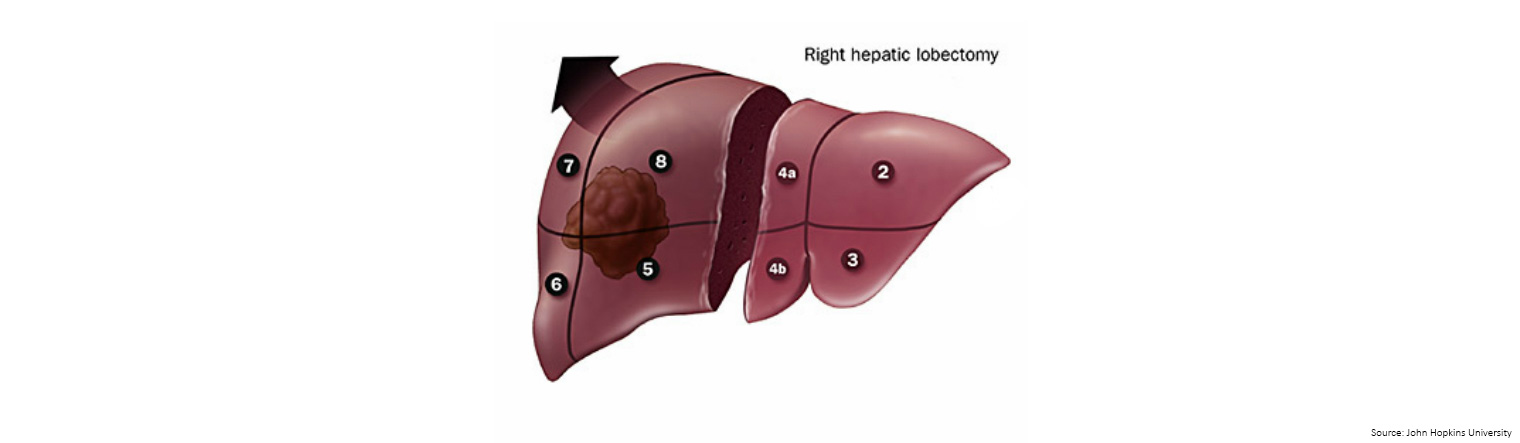

There are only four surgical units that lend themselves to controlled excision and they include lobectomy (right and left), trisegmentectomy (right and left), segmentectomy, and wedge resection as illustrated below.

Right hepatic lobectomy - right lobe which consists of two segments.

Left trisegmentectomy (also known as extended left hepatic lobectomy) - removal of the complete left lobe plus the medial segment of the right lobe.

Lateral segmentectomy - liver to the left of the falciform ligament (a ligament that attaches part of the liver to the diaphragm and the abdominal wall) in a single segment.

Once you go home

- you lose your appetite for a couple of weeks after liver surgery

- you feel some pain and need to continue to take the painkillers prescribed to you by your specialist

- you need to have a nap during the day. This is perfectly normal and is all part of the recovery process. It may take up to three months before you need to stop having a nap in the afternoon. It is also, however, important that you do regular, gentle exercise as it plays an important role in regaining function and strength after surgery

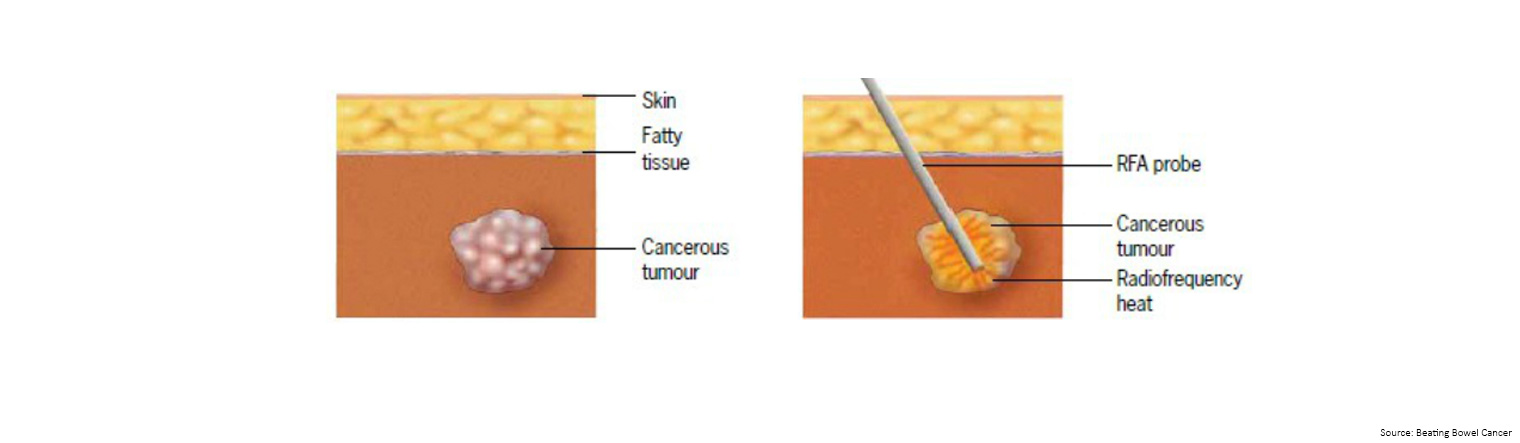

Radio frequency ablative therapy is a technique of heating up and destroying liver cancer, with the overall aim of controlling tumour growth in the liver.

Imaging techniques (e.g. ultrasound/CT) are used to guide a probe (needle) into the tumour, through which high frequency electrical currents are passed. This creates heat that destroys the cancer cells. 'Radio frequency' refers to the high frequency electrical currents. 'Ablation' means destroying.

You may be recommended RFA for the following reasons:

- you have more than one tumour in your liver

- the position of a tumour means it is difficult to perform surgery (for example, near a major blood vessel)

- You have other conditions that make surgery difficult

Research shows that RFA works best on tumours less than 3cm across, but it can be used on larger tumours. You can have RFA treatment more than once.

The treatment is given under a general anaesthetic. The surgeon/radiologist uses the scan to guide the probe (1-2mm across) into the tumour. The heat can be varied depending on the size of the tumour, and the time taken to treat each tumour is usually about 10-15 minutes.

Some patients experience side effects following treatment, which can include:

- discomfort/pain where you've been treated (for up to two weeks)

- feeling generally unwell for a few days; perhaps a raised temperature

- infection, bleeding or organ damage (rare)

Most people go into hospital the night before the procedure, and go home the day after. You will be given painkillers to take home and you will usually have another CT scan 6-8 weeks after the treatment to see how effective it was.

Whilst chemotherapy is a common treatment for metastatic cancer in the liver, chemotherapy alone is unlikely to provide a cure.

If the liver tumour is too large to operate on, you may have chemotherapy to try and shrink the tumour so it can be removed. If the liver tumour is small, you may have chemotherapy before and after the surgery.

Chemotherapy may be given to improve ability to undertake surgery, to reduce the number of tumour cells, or to slow their growth to provide symptom relief and extend survival.

'Down-staging' chemotherapy with/without targeted therapies

RAS biomarker test

It is becoming more common for patients who are being considered for certain drugs (or prior to entry into a clinical trial) to have their RAS status checked.

Tumours that are wild-type have been shown to be more responsive to certain treatments. Therefore, determining the RAS status of a tumour helps oncologists to choose the most effective treatment for each individual patient.

Visit Bowel Cancer Australia's biomarkers webpage for further information.

TACE is a treatment used to treat cancer that has spread or started in the liver.

Chemotherapy is injected directly into the vessels in the liver that are surrounding the tumour. Because the chemotherapy is injected into the liver the side effects experienced are much fewer.

When is the treatment undertaken?

This treatment is usually undertaken when the liver disease is the predominant disease and surgery is not an option. It tends to be used when the tumours are too large for surgery or if there are many smaller tumours. It can be performed numerous times to the same area or many times to target different lobes of the liver. It is always important to ensure enough functional liver is left to compensate for the area of liver receiving the treatment. The size and position of the cancer in the liver will determine how much of your liver is treated.

How is the treatment performed?

A catheter is introduced via the femoral artery in the groin and threaded directly into the hepatic artery of the liver. The chemotherapy is injected directly into the area of the liver that is being treated. The chemotherapy is mixed with an x-ray dye to allow the specialist to see where and how much chemotherapy is being delivered into the liver. Following the administration of the chemotherapy the tiny sterile sponges are injected through the catheter to temporarily close the artery. This will starve the tumour of a blood supply and prevent the chemotherapy moving away from the tumour and affecting other areas of the liver. The healthy part of the liver is still receiving its blood supply from hepatic portal vein.

What happens following treatment?

After the procedure you will have pressure placed on your femoral artery in the groin to prevent bleeding and you will need to lie flat for around four hours. The side effects tend to be minimal but they may include mild nausea/vomiting and abdominal pain, sluggish bowels, low grade temperature and hiccups. Medications such as paracetamol (for pain and low grade temp) and metraclopramide (for nausea/vomiting) may help with side effects. You will be required to stay overnight in hospital.

What follow-up should is required?

A follow up appointment with your treating specialist and a CT scan should be made between 6-10 weeks after your TACE treatment to assess how effective it has been. If there where multiple areas treated or a large tumour volume then additional TACE treatments may be required.

SIRT (also called radioembolisation) is a targeted treatment, which can be given alone or in conjunction with 'down-staging' chemotherapy.

The treatment involves millions of very tiny 'beads' (micro-spheres) being injected into the liver. Each bead, which is about one third the diametre of a human hair, is coated with a radioactive substance that gives out radiation specifically to the liver (concentrating mainly in the tumours) for about two weeks.

While treating patients with SIRT is increasing, it is only suitable for patients who have liver tumours where either the liver is the only site of disease or the liver is the major site of disease.

SIRT has no effect on tumours outside the liver.

Before SIRT can be offered as a treatment option, there are a number of other factors that have to be considered.

Most importantly, you need to have a sufficiently healthy liver that is working satisfactorily. This is usually determined by a simple blood test.

Patients receiving SIRT usually undergo two procedures. The first procedure is to prepare the liver for the treatment and involves a fine tube ('catheter') being inserted into a blood vessel in your groin area and passed up to the blood vessel taking blood to the liver. You would also receive a small amount of radioactive dye to check the blood flow between your liver and lungs, and vessels in your liver will be blocked to stop the micro-spheres traveling elsewhere in your body.

The second procedure involves receiving the micro-spheres, also via the tube in your groin area. This is typically done 1-2 weeks after the initial test is completed.

The treatment involves staying in hospital for between one and four days.

In terms of side-effects, many patients have abdominal pain and/or nausea which will normally subside after a short time with or without medication. Patients can also develop a mild fever for up to a week, and fatigue for several weeks. Patients are usually given medications when they go home, such as pain-killers to prevent or minimise the side effects.

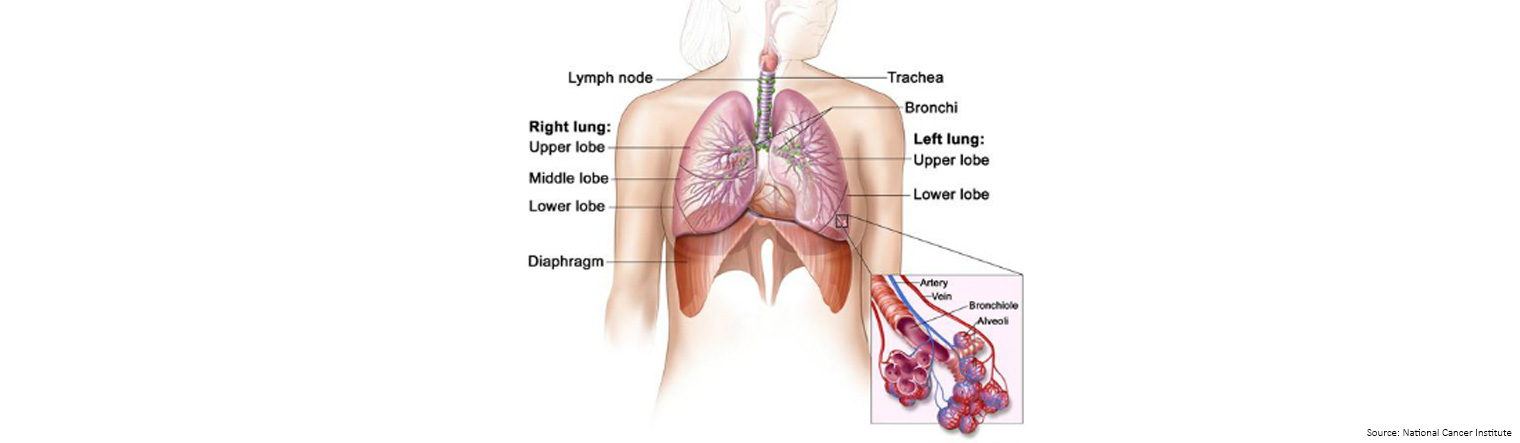

The lungs are a pair of cone-shaped breathing organs in the chest. The lungs bring oxygen into the body as you breathe in. They release carbon dioxide, a waste product of the body's cells, as you breathe out.

Each lung has sections called lobes. The left lung have two lobes. The right lung is slightly larger and has three lobes.

Two tubes called bronchi lead from the trachea (windpipe) to the right and left lungs.

Tiny air sacs called alveoli and small tubes called bronchioles make up the inside of the lungs.

The lining of the lungs is called the pleura.

Lung cancer is a term used to describe a growth of abnormal cells inside the lung - these cells continue to grow in an unlimited fashion until removed or treated.

The abnormal cells stick together and produce a growth or fluid. The abnormal cluster of cells is called a 'tumour'.

Cancer that starts and grows in the lung is known as 'primary' lung cancer. Cancer that has spread to the lungs having started as a 'primary' in another part of the body such as the bowel are called lung 'metastases'.

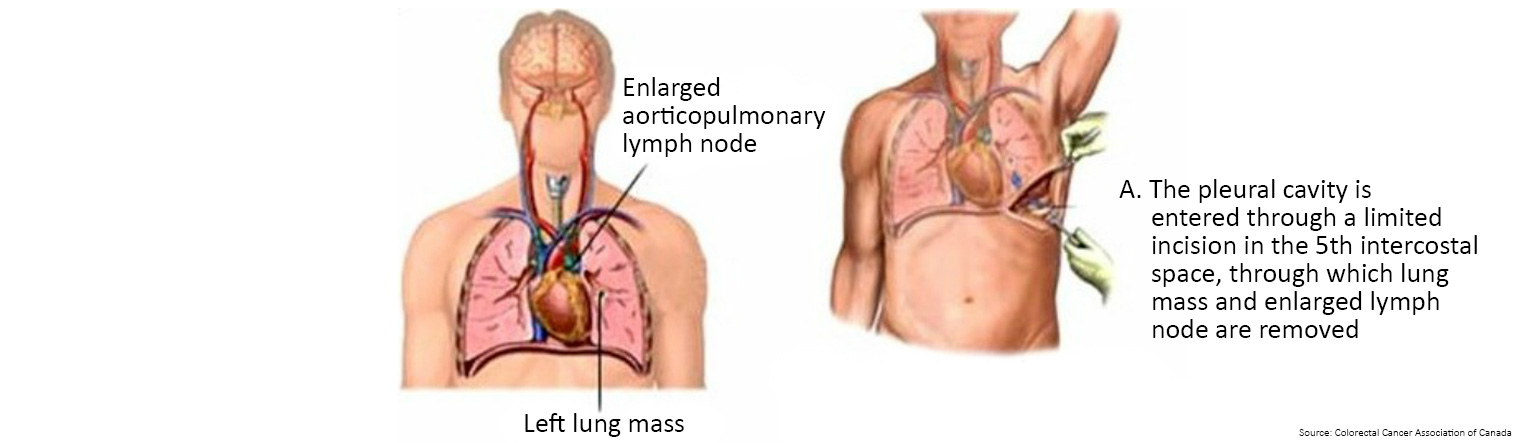

Bowel cancer can spread to the lungs, pleura, and lymph nodes surrounding the lungs.

- Chest x-ray: a chest x-ray may be taken to determine if the cancer has spread to your lungs and to provide information about the general health of your lungs, which is important when making treatment plans.

- CT scan: a CT scan creates a cross sectional, 3D image of the body. The scan gives detailed pictures of the tumour(s) and surrounding tissues and organs, enabling the doctors treating you to gain an accurate picture of the tumour, and its location.

- PET-CT scan: a CT scan can be combined with a PET scan which is a medical imaging technique which produces a three-dimensional, colour image of your body. When taken together, the results can be combined to show where there are any cell changes in the body, and whether the cancer has spread.

- MRI: magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) uses magnetic and radio waves (not X-rays) to show the tumour(s) in great detail and look at the blood supply to the liver. During the scan you will have to lie in the scanner for up to an hour, and, whilst it is very noisy, it is painless. Let the specialist know in advance if you are claustrophobic. You may be asked to drink a liquid 'contrast medium' before a CT or MRI scan, or be given an injection of a contrast medium during the scan (which may give you a hot flush for a few minutes). The dye travels to your liver to help produce a better image.

Treatment for lung metastases depends on the size, location in the lungs, extent of the cancer, as well as the patient's age, general health and feelings about the treatment.

The treatment includes surgical removal of part or the entire lung called pulmonary resection.

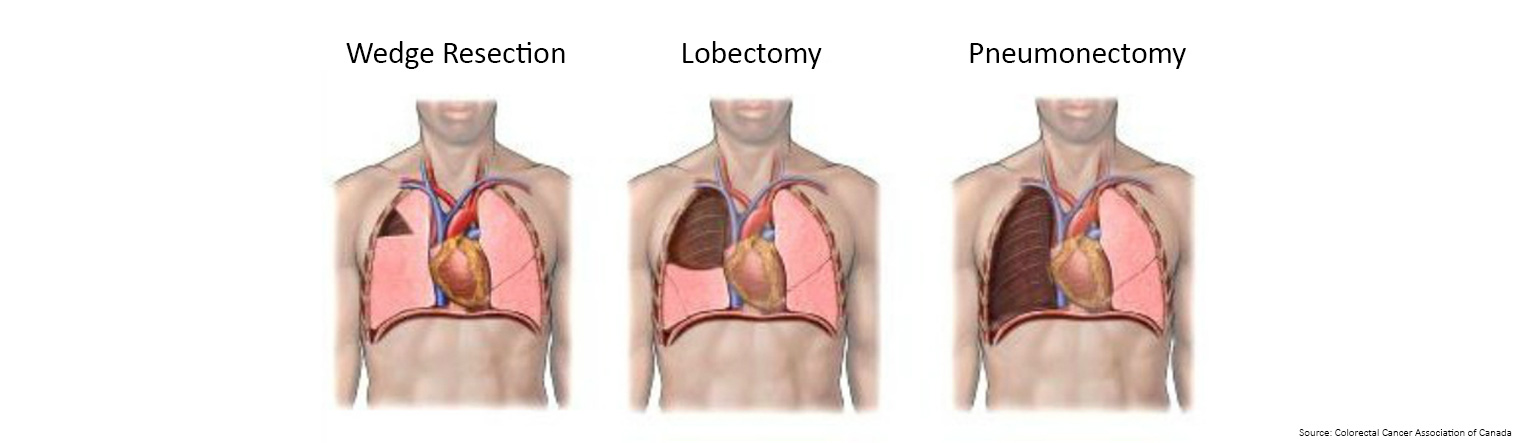

- An operation to remove a small part of the lung is called a segmental or wedge resection.

- An operation to remove a lobe of the lung is called a lobectomy.

- A pneumonectomy is the removal of an entire lung.

The surgeon will remove only the diseased portion of the lung. All types of lung operations require a thoracotomy which is an incision (cut) into the chest wall.

An incision (cut) will usually extend from just below your underarm to around the back. The incision is closed with dissolvable sutures (thread).

Thoracoscopy (minimally invasive thoracic surgery)

During thoracoscopic surgery, three small (approximately 2.5cm) incisions are used as compared with one long 15cm to 20cm incision that is used during traditional, open thoracic surgery.

Other names for this procedure include pleuroscopy or VATS (video-assisted thoracic surgery). It is performed in bowel cancer patients who have limited disease in their lungs.

Thoracic surgery procedures routinely performed using a minimally invasive technique include VATS lobectomy and wedge resection.

VATS lobectomy - Lobectomy (removal of a large section of the lung) can be performed using a minimally invasive approach. During video-assisted lobectomy, three 2.5cam incisions and one 7.5cm to 10cm incision are made to provide access to the chest cavity without spreading of the ribs. The patient experiences a more rapid recovery with less pain and a shorter hospital stay (usually 3 days) than traditional thoracotomy surgery. The surgical outcomes of video-assisted lobectomy are comparable to traditional lobectomy outcomes. Although minimally invasive approaches are considered for every patient, in some cases, patients who have a large or more central tumor may not be candidates for video-assisted lobectomy.

VATS wedge resection - a wedge resection is the surgical removal of a wedge-shaped portion of tissue from one, or both, lungs which can also be accomplished using this minimally invasive technique. A wedge resection is typically performed for the diagnosis or treatment of small lung nodules.

Abdominal (peritoneal) metastases can be more difficult to treat because of the way in which the cancers cells become attached to the outside of other organs and tissues in the abdomen

All the organs in the abdomen are contained inside a big sac or membrane called the peritoneum.

Bowel cancer can spread through blood and lymph circulation, or it can spread directly inside this sac if a tumour grows through the bowel wall before it is diagnosed.

Cancer cells can break off from the main tumour and escape into the abdomen, lodging between the lining (the peritoneum) and the other organs or tissues that are contained there.

When this happens, they can either be reabsorbed into the lymph system, becoming caught up in the lymph nodes, or they can become embedded and start to grow on the outside of other organs in the abdomen or pelvis.

Bloating and weight gain can be caused by fluid collecting in the abdomen as a result of cancer cells that have spread there. Recurrent bowel cancer that has spread into the abdomen or pelvis is more likely to be diagnosed via your routine blood tests and CT scans, especially in the early days following your initial treatment.

Investigations may include an ultrasound scan of the area, or an abdominal MRI scan or a PET scan.

Abdominal (peritoneal) metastases can be more difficult to treat because of the way in which the cancer cells become attached to the outside of other organs and tissues in the abdomen.

Treatment options available will depend on many factors, including which organs are involved and what other complicating factors might be present as a result of previous surgery (if this is recurrent disease).

If there are just one or two isolated metastases in an easily accessible position, your oncology team is likely to ask a general surgeon with specialist experience and training to review your case and give an opinion on whether an operation to remove them might be successful.

They may also ask other specialists to become involved if the metastases are affecting the bladder or kidneys for example, or the reproductive system in women (ovaries or uterus).

When bowel cancer spreads to the lining surfaces of the abdominal (peritoneal) cavity, it can be more difficult to treat successfully with traditional chemotherapies. However, if there is no other evidence of spread outside the abdomen, then a novel treatment, called hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC), may become an option for some patients.

The treatment is usually given during surgery when the surgeon will first remove all the visible cancer in the abdomen. While you are still under anaesthetic, this heated (hyperthermic) chemotherapy fluid is introduced directly into your abdomen (intraperitoneal), bathing all the organs and surfaces in the fluid for a maximum of two hours.

The HIPEC procedure is designed to attempt to kill any remaining cancer cells that may be left behind, but that cannot be seen.

This procedure is reserved for selected suitable patients.